Repurposing social media

Spotlight on emerging innovations in Nairobi’s informal fresh food retail sector

by Sarah D’haen, Louisa Nelle and Irene Fabricci | 2021-03-09

Lockdown and social distancing have led to a worldwide boom in online food and grocery delivery services, with Nairobi now being the leading city across Africa in terms of active online shoppers (Kanali, 2020) on platforms such as UberEats, Glovo, and Jumia Food. However, the use of digital solutions for the marketing and delivery of fresh food is not reserved for big supermarket chains and platforms alone. Our recent fieldwork in Nairobi’s informal settlements reveals a number of digitally facilitated business models used by informal fresh food retailers and urban farmers here.

Over the past two months, the SEWOH Lab team has, together with our local partner Muungano Wanavijiji, interviewed 53 informal retailers in Mukuru and Mathare, some of whom are also active as urban farmers. In this article, we share our first insights from Mukuru, were 20 of our 26 interviewees said they used digital tools for business purposes.

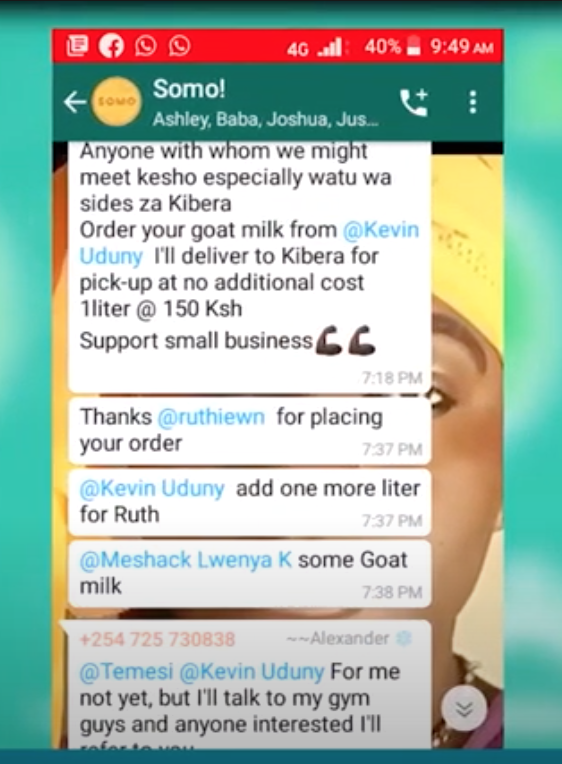

Most of the digitally active food retailers and producers that we spoke to reported that they use social media apps such as WhatsApp and Facebook to reach their customer base. In fact, three of them started exploring these digital tools during Nairobi’s lockdown in spring 2020, and quickly found themselves not only maintaining their customer base, but also considerably expanding it. It is likely that the social nature of these apps lowers the threshold for sharing information, by making it more accessible, and faster, compared to more formal or specialised online platforms and apps, such as Jumia. In addition, the personalised, word-of-mouth nature of social apps appears to make it easier to build trust, and for (new) customers to directly convey their orders and wishes to retailers.

A trusted medium

One retailer explains: I use WhatsApp in sourcing and when customers are placing their orders. It’s a great way to get customers. … I get customers by sharing with friends then friends share with others that’s how I network.

Screenshot of goat milk orders via a WhatsApp group (Source: Kevin & Sylvester’s Video Diary)

As a direct response to customer demand, some of the retailers in our sample have, for example, adjusted their range of products. This repurposing or retargeting of social media for business purposes by producers and retailers in Mukuru are a textbook example of social network marketing, where it is all about the direct relationship building with (potential) customers. The opportunities this represents have not gone unnoticed, and the strategy is also increasingly being picked up and explored by formal supermarket chains (e.g. in Nigeria).

Some residents in Mukuru are taking things a step further. Most of the interviewed informal retailers are tapping into WhatsApp for the sourcing end of business as well. We encountered digitally savvy retailers that activate family and friends based in the vicinity of (peri-urban) farms or key wholesale markets, to go check on product quality and negotiate prices on their behalf, in real time. Frequently, these retailers also are in direct contact with their suppliers and assess quality and negotiate prices based on videos and live images of the products.

This is illustrated by the experience of one retailer, who sources cabbages from Kinangop, approximately 120 kilometres North of Nairobi:

There are brokers in each ward because the farmers trust the brokers within their locality. I first call the brokers to tell him to look for stock and negotiate the prices. The brokers send many photos via WhatsApp. The broker moves around the farms to get the farmer with the best prices.

Another (female) retailer narrated a similar experience:

I get them [the mangoes] directly from the farmers …. We get them as four vendors, we are four cousins who decided to be ordering mangoes together but our businesses are in different areas [of Nairobi]…I have a friend there [in Ukambani, an area to the east of Nairobi] who goes to look for them, takes photos and send to us then we select what we want.

The adoption of social network sourcing, therefore, appears to be linked to its potential to significantly reduce transaction costs. This allows retailers to source from further afield and ensure a better price/quality ratio.

Adding value through social learning

Our interviewees also highlighted how they are using social media tools for knowledge exchange and (mutual) capacity building.

One poultry farmer and retailer told us:

Sometimes we communicate through the WhatsApp group we have with community health workers since most of the poultry farmers are community health workers. … We communicate when there’s a disease and when the chickens don’t lay eggs. Through WhatsApp we send pictures to each other of the sick chickens then seek advice on how to treat it.

We have observed similar initiatives elsewhere in Nairobi. During the Covid-19 lockdown, between April and July 2020, urban farmers Sylvester and Kevin [1] started receiving increasing enquiries about urban farming techniques through both their physical and their online business networks. In response, they created a dedicated WhatsApp group, connecting and teaching those in their network, interested in urban farming. They then invited veterinarians, agronomists, agroshop owners, and even civil servants from the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries to the group. The dynamic group, now counting more than 70 members, focuses on the open exchange of knowledge, where members can consult and advise each other on specific challenges and techniques.

A female retailer in Mukuru further explained that she is active on several local and international Facebook groups, including one bringing together Mukuru residents.

The groups are very informative because we share ideas, also we discuss matters pricing, chicken feeds and medicine. The advantage of being in these groups is that you learn new ways of rearing chicken and also when in doubt you can raise it in the group and get help. I only post chicken prices on Kenyan Facebook groups but for information and new ideas I have joined one from Nigeria and Ghana. The ones from Nigeria send you a link to join WhatsApp and then they send me documents via WhatsApp on chicken business. Nigerians rear chicken in large scale as compared to Kenya and they give more tips than Kenyan groups.

Digital tools and analogue social relationships

The inspiring stories above point to some insights as to how and what kind of digital tools could support some of the key food systems actors here in their operations. The interviews suggest for example, that the digital business interactions of the informal retailers are built on or facilitated by trusted (pre-existing) analogue social relationships, for example through living and working in the same locality. In fact, 17 of the 20 ‘digital’ retailers explicitly mentioned that they (only) digitally interact with business partners they “trust,” with whom “they already have a longstanding (trusted) business relationship,” or whom they know because “they run similar business locally.”

In this respect, the popularity, among our interviewees, of WhatsApp as the preferred tool for these interactions is perhaps also not so surprising. Designed to facilitate the direct relationship and social ties between individuals and groups, the (business) connections established through this tool require at the very minimum “via-via” (existing) trust relationships between the individuals connected.

We are excited to further explore these and other digital innovations in Nairobi’s informal settlements and to find out more about what kind of digitalisation makes a difference for local food systems and their actors here.

[1] Based in Mathare, another informal settlement to the Northeast of Mukuru, the two farmers participated in our Video Diaries initiative.

The interviews in Mukuru and Mathare are part of the SEWOH Lab project. Funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation (BMZ), this 5-year project, aims to identify digital approaches and their enabling organisational and institutional environment that contribute to achieving SDG 2. The SEWOH Lab’s applied research focuses on and works with vulnerable sections of society. The project’s Urban Nutrition Hub work stream serves to identify digital approaches and their enabling environment for making urban food systems work for the food insecure.

Urban Food FuturesFeb 09, 2026

Urban Food FuturesFeb 09, 2026Pushing the horizon: Urban farming and community-led innovation in Mukuru informal settlement

A small community-run greenhouse in Mukuru is offering insights into how controlled-environment agriculture can strengthen food security in urban environments under increasing pressure—and a look into the future of food systems in informal settlements.

Christian Sonntag, Emmanuel Atamba, Lumi Youm

Land GovernanceDec 18, 2025

Land GovernanceDec 18, 2025Land tenure, women’s land rights, and resilience: Reflections from CRIC23 toward UNCCD COP17

Our experts discuss what the exchanges at CRIC23 highlighted and revealed about the role of secure and gender-equitable land tenure in the UNCCD's work ahead of the 2026 triple COP year.

Frederike Klümper, Washe Kazungu

Urban Food FuturesDec 09, 2025

Urban Food FuturesDec 09, 2025The story of Mukuru's Urban Nutrition Hub

In Mukuru informal settlement, a safe haven for women has grown into the Urban Nutrition Hub, a multi-purpose space for nutrition education, training, and community development, demonstrating the potential of grassroots community-owned innovation..

Serah Kiragu-Wissler

Written by Sarah D’haen, Louisa Nelle and Irene Fabricci