Cheaper Food, Higher Costs: The Paradox of Nairobi’s Food Systems

Why are many staple foods in Nairobi often more affordable in informal markets? Our study uncovers the hidden costs, and who must bear them. Can the city build a food system that’s both affordable and fair—for consumers and the people who feed them?

by Christian Sonntag, Emmanuel Atamba, Lumi Youm | 2025-09-29

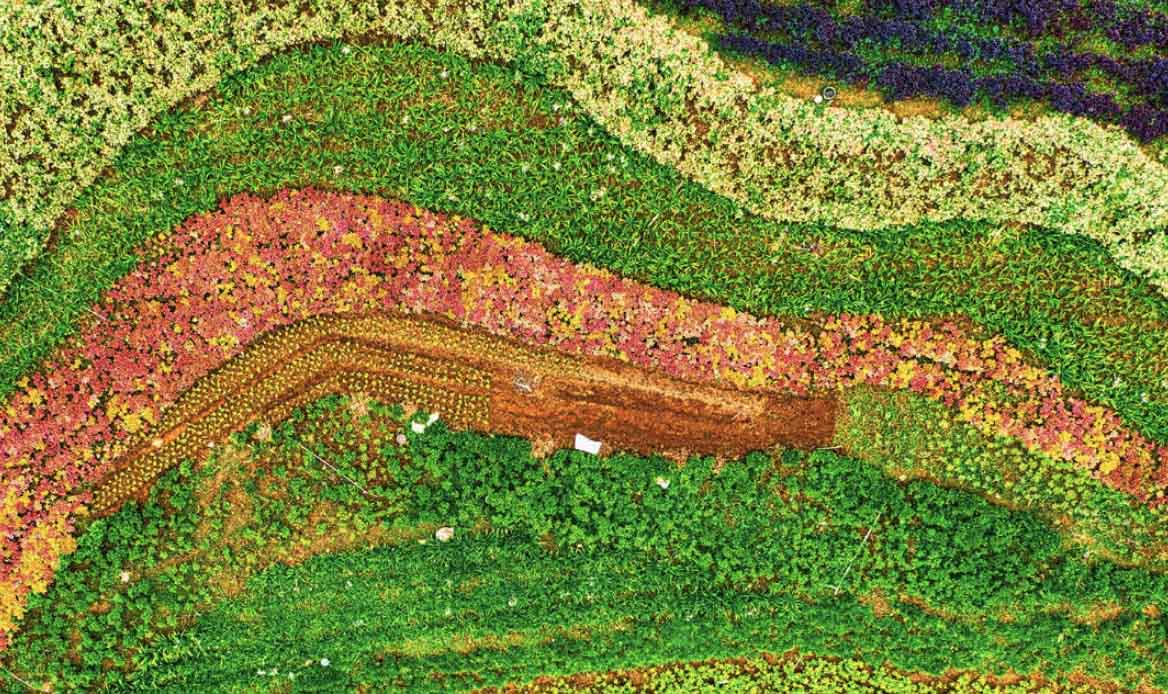

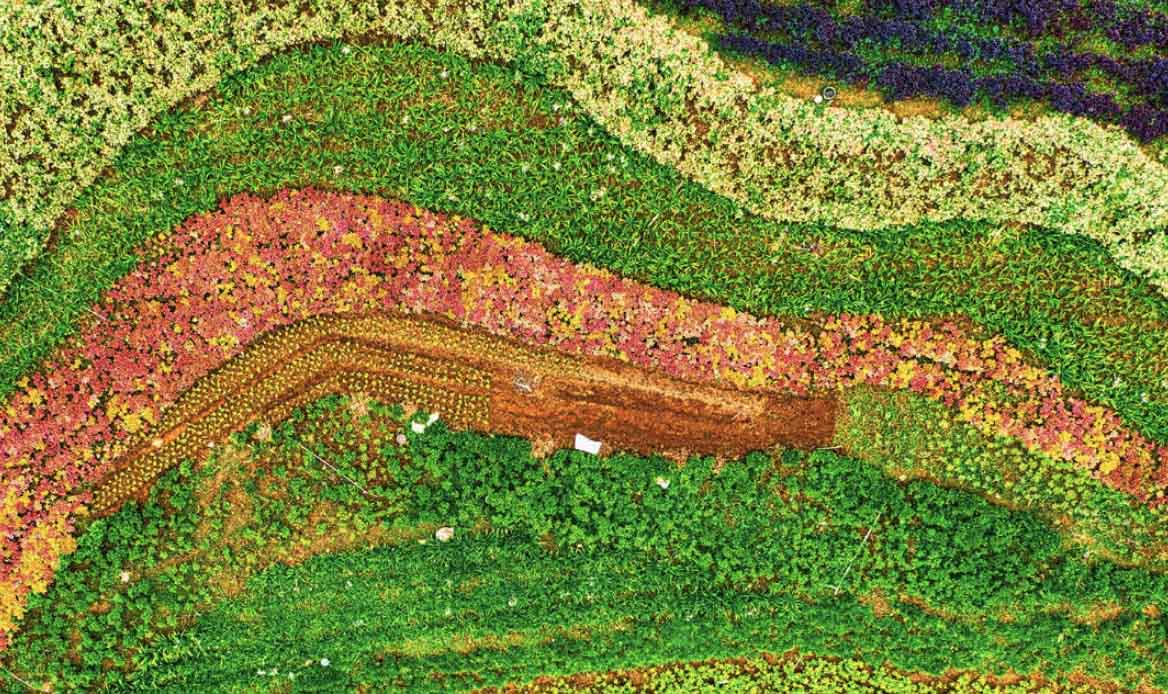

A vendor sells tomatoes at an informal market. Photo credit: Akiba Mashinani Trust.

Food prices in Nairobi are rising faster than incomes, and basic nutrition is slipping out of reach for many. In the past year alone, the price of maize flour has increased by 13 per cent, while tomatoes have soared by 38 per cent (KNBS, 2025). For many households, every shilling counts.

Take maize flour, the key ingredient of ugali—one of Kenya’s most basic staples. The lowest prices one can find, whether loose or fortified, are at posho mills (local milling facilities) in informal settlements: about KES 63 per kilogram (≈ €0.42). At a supermarket, prices range from KES 65 to KES 75 per kilogram. Similarly, one egg costs about KES 15 in informal markets, but KES 22 in formal retail. For Nairobi residents faced with tight budgets, the choice is clear.

But why does the same food cost more, or less, depending on where you shop? And what does this mean for the city’s ability to feed its people?

Tracking the cost of a meal

Recent research by TMG Research and Akiba Mashinani Trust (AMT) examined food affordability using a food basket study in the informal settlement of Mukuru, Nairobi. The study tracked the cost of 23 commonly consumed staples, including maize flour, vegetables, fruits, and animal products, and compared prices between informal markets and formal retail outlets.

The results were striking: food from Nairobi’s informal markets was, on average, 13 per cent cheaper than in supermarkets and other formal outlets, despite the economies of scale and other advantages of formal retail.

Typically, fruits and vegetables, eggs, cereals, dry foods (such as beans, yellow beans and rice), and cooked foods (such as githeri, mandazi, and chapati) are sold at lower prices in informal markets. Even for items generally cheaper in formal retail (such as milk, sugar, and processed or packaged foods), vendors offer unmatched flexibility in quantity, price negotiation, and credit. For residents of informal settlements, informal vendors are much more accessible than formal retail outlets—which are often too far and too expensive.

The hidden subsidy behind low prices

How can informal markets consistently offer lower prices than formal retailers for many of the same products? The key reason lies in the discounting of labour in informal food trade.

Informal traders discount labour costs by paying themselves low wages that often fall below set minimum wage rates. They also often rely on family labour, for which only nominal compensation is provided, effectively resulting in subsidized labour. They typically do not offer benefits such as sick leave, annual leave, pensions, or workers' compensation, further reducing overall labour and overhead costs.

Behind the lower prices lie long days of work without contracts, no safety nets when illness strikes, and constant harassment or threats of eviction from city authorities. Vendors operate in crowded, poorly serviced spaces with little protection from weather or sanitation risks. They often juggle childcare on the job, with children napping under stalls or helping run the business after school. Many also depend on informal credit chains, leaving them vulnerable to losses when customers cannot pay.

This reveals a paradox in the city’s food systems: informal markets make food more accessible for many, but they also rely on a hidden subsidy of unpaid risks and vulnerabilities.

These invisible sacrifices are what keep food within reach for many of Nairobi’s residents. In effect, food security for consumers rests on the insecurity of those who supply it.

The unseen pillar of food security

Because of their affordability and accessibility, informal markets are central to Nairobi’s food security. For many residents, especially in low-income neighbourhoods, informal vendors are the primary and often only source of food.

Informal markets provide many public goods: they ensure affordable access to staple foods, safeguarding the right to food. They sustain livelihoods for thousands of vendors and producers, adapt quickly to local needs thanks to deep community ties, and provide help in crises when formal systems falter.

However, these public goods should not come at the expense of vendors' own safety, livelihoods, and well-being. Like workers in formal retail, informal vendors deserve fair compensation for their work, personal safety, and labour and social protection.

How, then, can we improve the conditions of informal vendors while maintaining the affordability of the food they sell?

The way forward: bridging the divide

Building a resilient, inclusive, and fair food system that provides affordable food for all while safeguarding informal vendors’ well-being and livelihoods requires concerted efforts and a shift in how policymakers view informal markets. Rather than criminalizing or displacing informal vendors, public investment is needed to strengthen their capacity to provide safe, affordable food while improving conditions for people who work in and rely on these businesses. Specific interventions could include:

Improving market infrastructure: enhance access to clean water, sanitation, drainage, lighting, and waste management for small food businesses and informal vendors

Simplifying and reducing licensing costs to reduce barriers for small-scale vendors

Expanding social protection for informal workers, including health insurance and income security measures

Fostering collaboration between formal and informal actors to ensure food safety and traceability without undermining affordability.

Investing in an equitable food future

The future of Nairobi’s informal food systems is deeply tied to global ambitions such as Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger. Achieving such goals requires recognizing informal markets as an essential bulwark against urban hunger. Far from operating on the margins, informal vendors hold Nairobi’s food system together. Flexible, adaptive, and deeply rooted in their communities, they are quietly sustaining the city in ways that formal systems cannot match. A more inclusive, equitable, and resilient food system must acknowledge their contribution and invest in their future. By working with informal vendors, Nairobi can build a just and affordable food economy that delivers on the promise of Zero Hunger while leaving no one behind.

Land GovernanceJun 26, 2025

Land GovernanceJun 26, 2025Did 2024 - the year of the triple COP - change anything for land rights?

What did this “triple COP” moment really deliver for land rights? Can we keep the momentum up to advance gains made and push for bolder action?

Frederike Klümper

Urban Food FuturesJun 20, 2025

Urban Food FuturesJun 20, 2025Working with informality: A hidden path to Zero Hunger

Global progress on Zero Hunger is faltering, but a powerful, overlooked solution exists: working with informality. Supporting the networks already feeding cities and sustaining communities can drive progress not only on hunger, but across multiple SDGs.

Jes Weigelt

Land GovernanceMay 29, 2025

Land GovernanceMay 29, 2025Land rights are a tool for justice in carbon markets

Explore how carbon credit projects threaten people's land rights, as well as concrete policy pathways to reverse this alarming trend to achieve climate justice.

Joanna Trimble